Ok, so I think that it’s time to start using this blog for what it was originally set up for – palaeo related blog ranting, or ‘outreach’ as I will call it on my CV…

I’ve been meaning to get back to science blogging for a while now, and this time I will do my best to not delete everything in a blind mad panic about not getting enough actual work done… former followers of matt-baron-picking-bones may remember my lengthy accounts of field work and tedious tracts on why I don’t like theropods getting all the press etc.

Anyway, I’m back, and to kick things off on blog 3.0 I’ll be quickly talking about my first ever publication, which I published in PeerJ all the way back in 2015, when I was still young, wide-eyed and bushy tailed…

For fans of historic taxonomic debates on long dead fish between Victorian Era scientists, or anyone that love stats, this paper is for you – it was titled “An investigation of the genus Mesacanthus (Chordata: Acanthodii) from the Orcadian Basin and Midland Valley areas of Northern and Central Scotland using traditional morphometrics” and can be found here.

It started as my undergraduate research project at Aberdeen. The late and great Prof. Nigel Trewin, an expert in all things related to Scottish fossils, kindly offered to supervise me and gave me the keys to the vast collections in the museums he curated. We talked about potential projects that could be done within the two term time-frame and quickly got on to talking about a little fish called Mesacanthus.

Mesacanthus is a common(-ish) fossil from the Devonian rocks formations of Northern Scotland. Its an acanthodian, which means its somewhere on the fish family tree near the base, possibly close to sharks, possibly not – basically the group is just considered a waste-basket term for primitvey looking fishy things with spines sticking out of them from about 400 million years ago. Mostly, their fossils are a bit bent and twisted and decayed, but some are nicely preserved, owing largely to the fact that they lived in a deep lake, the bottom of which went through periods of being anoxic = so uninhabitable that dead stuff that sinks doesn’t get destroyed by scavengers and doesn’t decay much before burial…

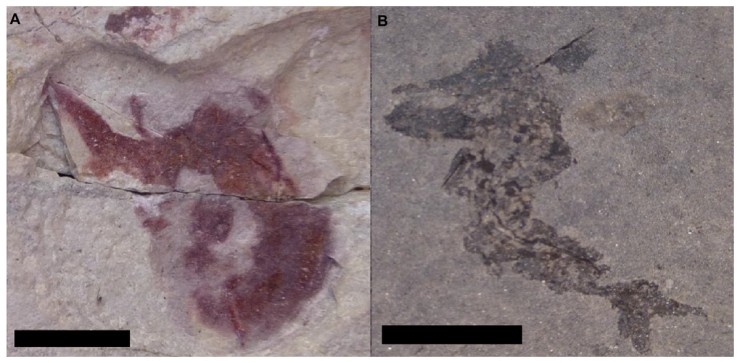

Here are some fish…

So the problem was, some people in the 1800s had looked at all of these fish specimens and had decided to group them into different species based on a supposed difference in ratios between length, width, fin separation and scale patters. Nigel wasn’t so sure, and so i was charged with the task of collecting all the measurements from as many specimens as I could see. This involved going down to Edinburgh too, where Stig Walsh worked tirelessly to keep bringing me a seemingly endless supply of these fishy smears on rocks. In total, I think I measured a couple of hundred different fish.

For my undergrad project I ran some basic stats and, from what I had measured, found no significant differences between the specimens that came from the same ‘time-bin’ or locality. There was significant difference between the older and younger specimens. We then found the same pattern when we looked at the scale arrangement in the specimens.

Unfortunately, we ran into a little bit of a snag – the holotype specimens (the one the genus and species names are pinned to as the ‘ideal’) were missing… this meant we couldn’t analyse these key specimens and couldn’t therefor prove or refute the taxonomic opinions of the Victorian collectors who had grouped them into different species…

Fortunately, after graduating Aberdeen and getting an offer of a PhD project at Cambridge and the NHM in London, I found myself with access to more material and more resources… with a lot of searching through dusty old drawers with the help of Emma Bernard at the museum in London, we were able to track down one holotype and match it to a drawing made by none other than Richard Owen (founder of the NHM and Patron Saint of of comparative anatomists everywhere)… I was then in a position to add the specimen to my data…

After sending a lot of emails to various museums around the UK, I eventually got a reply from one curator of a country house and museum in the Lowlands of Scotland, saying that she thought the holotype of one of my specimens might actually be in a cabinet in one of their rooms – the Lord of the house was a collector of curiosities apparently… She kindly sent a photograph and, ta-da, it matched the original drawing by Agassiz… so that got added too…

The remaining holotypes were not so easy to add… however, from the original figures and descriptions, some of the key measurements for the fish could be taken, giving me just about enough data to include them in my analyses…

Anyway, to cut the long story short, with new stats methods and a lot more looking at scales down a microscope, I came to the same conclusion as Nigel Trewin had back when he first sat with me in the museum in Aberdeen, pouring over the specimens in the teaching collection… There’s probably actually only two valid species in all of the known specimens, one from the Lower Devonian (older) and one from the Middle Devonian (younger)… and the younger ones were ‘fatter’ and had the lake to themselves basically… which hints at some kind of transition across the boundary, and perhaps a shift in the genus’ position in the ecosystem… but lets not arm wave…

here are some more pictures of fish…

by

Dr Matthew Grant Baron